If Ralph Waldo Emerson had Twitter back in his day of the 1800s, his profile would be something like: @RalphBeReal: poet, gardener, curator of common sense, nature lover, & kickass thinker. He’d follow folks like Robert Frost, Margaret Fuller, Walt Whitman, Johann Goethe, Robert Richardson, and David Letterman.

Emerson was to rescue me from the Twitter scrublands, where I've been getting all turned around and off track. But, he didn't. Just the opposite, reading Emerson's notions of some two-hundred years ago, I realized this: Ralph would be tweeting with us.

For one, as much as his writing sounds stuffy, Ralph was into street-level language. He chose one-syllable words when possible and he opted for strong nouns over fluffy adjectives. He wanted his writing to sound as if it were a conversation. So, yeah, he’d do Twitter.

Hashtag Nature

Besides, Emerson would have liked how Twitter keeps us direct: 140 characters or no tweet for you.

But, wait. Twitter has a lot of people retweeting opinions about opinions. Sometimes, as Twitter readers, we climb into the role of archeologist and we still can’t quite excavate a tweet’s origin. Who's the real deal? Who's a poser?

This would peeve Ralph; he prized original accounts and first-hand experiences. He’d read your poem or your blog. But, share a blog that was an opinion of another’s work? Say, a critique of another’s garden? No.

Go outdoors and sow a seed yourself. Then, write about that. No kibitzing from the fence. “Do your own quarrying,” Emerson would tweet. And, since a hashtag makes a topic more searchable, he'd hashtag his point: #Nature #GetOutdoors.

Lists Make You Listless

With a likable hint of grumbling, The New York Times Book Review’s Editor Pamela Paul tweeted, “Phew! I’m all done reading year-end lists.”

The best-of-2014 this, the worst-of-2014 that. Our minds crave rank and file, and we cook up more than we can stomach. Emerson would tweet: “Skip others’ lists. What are your own thoughts?”

Blank? No worry. Add individualism to your new year’s intentions. Ralph can tweet you a short ow.ly hyperlink to his 1840’s compilation Self Reliance, a great antidote for any Twitter hangover.

Because, see, the result of relying on others’ lists is boredom. Therapists like myself will ask clients who feel blah and listless, "What lit you up when you were little?" Often, a person can’t recall. Their basic selves got boxed away in the basement. But, going back that far puts us at a time when others’ viewpoints didn't crowd out our own - at least, not as much.

“What lit you up when you were little?”

The Curious Venus Flytrap

Asking myself this question, I find I’m eight years old again, leaning over a small venus flytrap plant. I cared for it on the shaded sill of my childhood bedroom’s single window. The sun rested delicately on the plants' frailness.

The sight softened my gripping worry about the next-day’s homework assignment; I wanted to get my handwriting exactly right, each letter's line and curve identical to the line and curve of the letter I’d drawn before it. (I know.)

But, the venus fly-trap! Would it really eat a fly? With conflicted feelings, I’d feed it foreign objects but no bugs. The mouth-like leaves would close around the sacrificial sweater lint. But eat it? If it had been a real fly, how would it actually eat it? So, there in my room, I discovered what fascination feels like. It felt like curiosity, and I learned that plant life did that for me.

Being followed. Creepy, right?

But, hey, never mind that. Grow up fast and pay attention to adult concerns: How many followers on Twitter do you have?

Gah! Emerson would be peeved again, tweeting: “Happy is he who looks only into his work to know if it will succeed, never into the times or the public opinion...”

I bet Emerson would have followed Pamela Paul on Twitter. He’d value her take on culture. He’d even thumb-up her New York Times essay How to Be Liked by Everyone Online, where she writes:

“I’ve never liked the idea of being followed. Late at night walking from the subway, I’m always on the lookout for lurkers...Followers are for religious leaders, for gurus, for motivational speakers, and I am none of these things...Girls with followers scared me. Followers can turn on you; they travel in packs...Yet now I am told every day, sometimes by the minute, that someone is following me, and that this is good news...”

Now, we want to be followed. We want to be wanted. I see Emerson rubbing his tired brow, tweeting: “Every man is wanted, but not wanted much.” So, can we rid ourselves of sites like Klout and SumAll? More than likely, these are invasive weeds in our fields of self contentment.

Plus, to lean on Pamela Paul one last time: “To have something liked online is not as great as having something actually liked. It doesn’t even necessarily mean someone enjoyed it - it might simply mean, ‘Got it.’ ”

Twitter Love

We do need to lean on each other sometimes. It’s the wellspring of The Tipsy Tomato. And, at this writing, I needed someone to lean on. My thoughts were all jumbled up. My aspirations were a seed packet spilled before I even got to the garden’s gate.

“My aspirations were a seed packet spilled before I even got to the garden’s gate. ”

So, I leaned on Emerson, who turns out to be an early advocate of TwitterLove. I first learned about TwitterLove from the British gardener and journalist Alexandra Campbell. Her site is cheerful looking: perky dots for petals as its banner and, on the blog page, an image of 1950’s birds chirping “Hello, Lovely” and just plain saying “tweet” like garden birds do. So, I wanted to see what this smiling woman had to say. Her notion is worth, uh um, well yes, retweeting:

TwitterLove is when you’re more interested in supporting one another than in promoting yourself. You reply to others' ideas and questions; you thank people; and you encourage them in their gardening pursuits. As an example of what is not TwitterLove, Campbell tweeted about a (nameless) garden celebrity who, despite thousands of followers, only follows three people. Humph.

Acreage of Wild Self-Interest

Wild self-interest crowds out a lot of Twitter’s acreage, but not all of it. My first TwitterLove community was @OldHorts, which is a welcoming group in the U.K.. Across the big pond from where I live in New York, we chat about selling ugly veggies, the beauty of Scottish fungi, and the human rights of Mexican tomato farmers.

Solitary Confinement

My profession as a therapist and my need for gardening can make me too solitary at times. Plus, there’s only so much garden talk my hubby ought to endure in the evenings. So, between garden chores, clients’ appointments, and spotty weather, I can have a quick chat with fellow gardeners whom, without Twitter, I would never be able to enjoy.

Sorting out the use of Twitter for himself, Emerson would marvel at the potential: Our minds, boundless beyond our own solitary fences. I imagine he would tweet about this, too - though, of course, it's for his own mind to experience and decide.

“Our minds, boundless beyond our own solitary fences. ”

Photo by The Tipsy Tomato, Venice Morning

Acknowledgements:

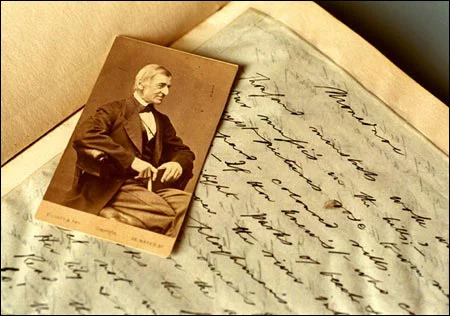

Photo at top of this page is from the Harvard Gazette and the Houghton Library's collection of Emerson materials; Staff photographer: Rose Lincoln. Original photo: Ralph Waldo Emerson, circa 1848, with the original manuscript of his poem "Monadnoc," circa 1845.

A longer version of How To Be Liked By Everyone Online, written by Pamela Paul, appears in the Dec. 21 paper version of The New York Times, p. 10 of the style/culture section, titled How To Speak Internet.

Emerson quotes are thanks to Robert D. Richardson's book, First We Write, Then We Read (University of Iowa Press, 2009)